I’m Heather, the founder of Just Kai. I’m super-keen to make sure the food I eat is free of forced labour or child labour. That’s actually how Just Kai started - with me trying to make sure my own food is slave free.

But I have a problem. My husband was born and brought up in Thailand - he’s always loved Thai food, and I’ve come to love it, too. But Thai food uses a lot of seafood - especially the ubiquitous fish sauce! - and the Thai fishing industry uses a lot of slave labour.

I thought it might be useful to share what we’re doing to try and square that circle - trying to enjoy a cuisine made with many risky ingredients, but to do so with a (reasonably!) clear conscience! Hopefully it’ll be helpful, whether you love Thai food or not. After all, many cuisines are big on sea food, so our approach to Thai food might give you some ideas how to keep enjoying your favourite cuisine as well - be that Mediterranean, Pasifika, Chinese or West African!

Mostly I’ll list what we’re doing, ingredient by ingredient, but I’ll start with some thoughts on the principles that guide our choices.

Table of Contents

Guiding principles

When trying to cook slave-free, the first thing we tend to think about is: is this an ingredient we use a lot of? If it’s something we tend to use in most meals (like rice or fish sauce) then we’ll want to find a slave-free option. Similarly, if it’s something that will be a major ingredient in a particular meal (like fish or prawns), we’ll be wanting to find out if it’s likely to have slavery in its supply chain.

For more minor ingredients that are used infrequently, we generally aren’t so concerned whether they are slave-free or not - although if we come across a slave-free version we’ll definitely choose that. The exception is those minor ingredients where we’ve learned that they’re at very high risk for serious labour abuses. That’s the case for cashew nuts, for example; we only buy fairly traded cashew nuts, even though we don’t use them often and they’re hardly ever the main feature of a meal.

When we learn that an ingredient we use a lot has a high risk of slavery in its supply chain, the next thing we want to know is: can we find a slave-free version that’s produced in a high-risk location? If people are producing slave-free products in a high-risk location, we want to support them! Then they’ll be able to draw business away from the slave-produced products (making it less economic to enslave people) - plus they’ll be able to hire more people, meaning less people are likely to be drawn into slavery.

So, for prawns, which are generally used as a major ingredient and which are at high risk of having slavery in their supply chain, we tend to buy Kingfisher prawns (which are produced in Thailand - a high-risk location), rather than Ocean Pearl prawns (which are also slave-free, but come from Australia).

If we can’t find a slave-free version from a high-risk location, our next choice will be simply a slave-free version (that’s what we’ve settled on for fish), or a substitute (what we’ve done for dried shrimp). If we can’t find either of those, then we’ll go without (which is what we’ve ended up doing with squid).

So, on to the individual ingredients, and the various decisions we have made.

Rice

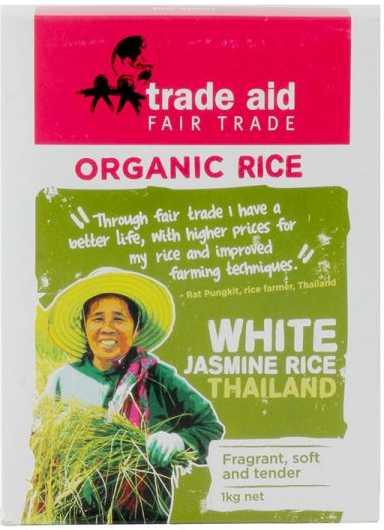

You can’t have Thai food without rice! Any jasmine or glutinous rice sold in New Zealand has generally been produced in Thailand. Neither forced labour nor child labour has been found in the Thai rice industry, so you can buy any brand of either kind of rice without supporting those abuses.

However, a major issue for rice farmers are low and unstable prices, which lead to many rice farmers living in considerable poverty. If you want to buy jasmine rice where you can be confident the farmers earned a living income, buy from Trade Aid. They sell both white and wholegrain jasmine rice in 1kg and 5kg packets.

We don’t know of anyone selling fairly traded glutinous rice, but we still buy glutinous rice regularly as we’re confident any brand we buy is unlikely to have been produced using severe human rights abuses.

Protein

Prawns

Sadly, forced labour and child labour are huge issues in the prawn industry: abuses occur at every stage of production, from the catching of fish that go into prawn feed through to the prawn farms and then the facilities that deshell and devein the prawns. When it comes to deshelled farmed prawns, we only trust one brand to be slave-free: Kingfisher prawns (sold at PakNSave and New World).

Kingfisher also produces prawn cutlets which we’ve enjoyed with glutinous rice.

If you’re OK with shelling your prawns yourself, another slave-free option is unprocessed prawns from Ocean Pearl.

Pork and chicken

This is the only place where I’m not comfortable with our current choices!

We learned a couple of years ago that pigs and chickens (like salmon and prawns) are fed on fish meal. We haven’t looked into this further, so we don’t know whether all farms do this or only some, and we certainly don’t know whether anyone feeds their livestock on fish meal that’s made from responsibly-caught fish. At this stage we are continuing to buy pork and chicken but aren’t taking any steps to make sure it’s been fed on slave-free feed. I’m hoping in the future to at least do an assessment to find out how risky these meats are from a slavery point of view, but haven’t got there yet.

Fish

Fish is at very high risk of having slavery in its supply chain. However, that risk is low if:

- the fish is caught in a country with strong and well-enforced labour laws (like New Zealand) AND

- the fish is caught close to land (as people on those fishing vessels have frequent access to land and so can relatively easily access contact the police if they are subject to slavery).

We intend to research the New Zealand fresh fish market in the future and hope to find slave-free options for higher risk fish at that time. In the meantime, we are sticking to fish caught inshore in New Zealand waters. This includes:

- snapper

- kahawai

- blue cod

- tarakihi

- flounder

- gurnard

- trevally

- grey mullet

The photo is an (admittedly Vietnamese) sweet and sour soup we recently made with grey mullet. It was delicious - and grey mullet was a remarkably affordable choice at our local supermarket.

Squid

Squid is often caught using slave labour - the only conviction for slavery in New Zealand waters occurred on a squid boat, and there have been many such cases overseas. For this reason we’ve decided we’re only willing to buy squid we’re really confident is slave-free - it’s a high-risk product and, in the dishes where it’s used, it’s a major ingredient. Sadly our research on the squid industry thus far hasn’t turn up any squid brands we can be confident are slave free, so we no longer use squid in our Thai cooking.

Beef

We very much enjoy the occasional Mussaman curry, and always make that with beef. Unlike pigs and chickens (and some dairy cows), it seems that beef cattle mostly eat what’s growing in their paddock (rather than a ‘feed’ as such). That, plus the fact that fresh beef sold here seems to always have been grown in New Zealand, means that beef is at very low risk of having slavery in its supply chain. We consider any beef sold here to be slave free, and simply buy whatever is convenient for us.

Tofu

We’re not big on tofu so tend not to use it, but from a slavery perspective we would be happy buying any tofu. The soy bean industry is fairly low risk for slavery, and most tofu sold here is made in New Zealand so the manufacturing process also tends to be low risk.

Flavourings

Fish sauce

Fish sauce is ubiquitous in Thai cuisine - sprinkled directly on rice and added to most dishes. It only has two ingredients: fish (typically small forage fish like anchovies), and salt. The fish are layered with salt in large containers and left to ferment for several months, then the liquid is removed and bottled.

Unfortunately, the small, low-value fish used in fish sauce are extremely likely to have been fished using forced labour. We haven’t been able to find a brand made with slave-free fish, so we’ve gone with a decent fish-free substitute.

There are many recipes on the internet for fish sauce alternatives that are made with seaweed. We tried several of these, but they didn’t taste right at all. Then we came across Kip, a vegan Thai food enthusiast, who said that the key was to use something fermented - as the fish sauce flavour mostly comes from the fact the fish are fermented, rather than it having a ‘marine’ flavour. Based on that insight, we developed the following recipe:

- 300 g fermented black beans (also called salted black beans - look for them at a Chinese supermarket - they could be in a bag or in a tin)

- 4 cups water

- 2 cups light soy sauce

- 40g dried shiitake mushrooms (it doesn’t matter if they’re whole or sliced - your Chinese supermarket should have them)

- 160g salt (a bit over 1/2 cup)

Bring all the ingredients to the boil, then take off the heat and leave overnight. The next day, strain thoroughly (pass it through a fine cloth, squeezing well to get all the liquid out) then boil it again. This time, simmer for 10 minutes (this makes sure the fermenting bugs are dead - otherwise it will keep fermenting in the bottle and your bottle may explode!) then pour into a measuring jug and top it back up to 1.5 litres (6 cups) with boiling water.

It should now keep fine at room temperature for a year or two. I seal some of it into sterilised 500mL bottles and put the rest in a squeezy bottle in my pantry.

It doesn’t taste the same as fish sauce, but it’s a ‘good enough’ substitute. When we’ve used it in recipes, people haven’t noticed the difference, although you can definitely taste that it’s not the same when you sprinkle it straight on rice.

If you don’t want to go through the hassle of making your own fish sauce substitute, for things like mashed egg, a very small amount of miso paste also works reasonably well. Some Asian stores also stock vegetarian fish sauce - we’ve recently tried this one and its a reasonable substitute, although we prefer our homemade version.

Curry pastes

Thai curries generally start with frying some pre-made curry paste - and pretty much all curry pastes have shrimp in them. The only common exception is yellow curry paste.

What to do? Shrimp is, like the small fish used in fish sauce, an ingredient extremely likely to have been produced with slave labour.

For this one, we’ve carried on using curry pastes as before. I’m not entirely comfortable with this choice, but here’s our thinking.

Unlike fish sauce, in curry pastes the shrimp is usually a minor ingredient, right at the end of the ingredient list. Also, although we use fish sauce widely in our cooking, we generally only use curry pastes when we’re making actual Thai food. So, between us not using them very often, and the risky ingredient being quite a minor ingredient, we figure our contribution to slave labour from buying these pastes is pretty small. Also, unlike fish sauce, making our own curry pastes felt really hard - they have many ingredients and need to be simmered carefully to come out right.

Putting all that together, it didn’t feel worthwhile to find a slave-free alternative to this one. For the same reasons we still keep Worcestershire sauce in our pantry, even though it includes anchovies in its ingredients and we haven’t found a slave-free version. Again, it’s something we use rarely, it’d be very complicated to make ourselves, and the anchovies are a minor ingredient.

Coconut milk and cream

The coconut industry doesn’t have an issue with forced labour or child labour, so any brand is fine from that point of view. However, it is an industry where farmers have very meagre and unstable incomes, so it’s good to support brands that pay a decent wage if you are able.

Recently Just Kai did some research on the coconut industry, and we were delighted to find that our favourite brand of coconut cream has an excellent human rights record. We were already pretty much only buying Kara, but are happy to be able to comfortably continue to use it!

An even better option would be the fair trade coconut milk from Trade Aid (available in some supermarkets), but we’re comfortable that Kara’s workers are being treated fine and we prefer coconut cream over milk, so we’ll be sticking with Kara.

Dried shrimp

We pretty much only use dried shrimp to make som tam (which we make with carrot - the authentic vegetables are much too expensive here!). As we got to the end of our last jar of dried shrimp, I started looking for an alternative. Shrimp is one of those ingredients almost certain to have involved labour abuse somewhere along its supply chain. With it being such a significant ingredient in a dish we prepare reasonably often, I wasn’t OK with carrying on using it.

We were delighted to find that an Australian company, Red Lotus, makes a fermented bean shrimp paste substitute. Like our home-made fish sauce, it doesn’t taste identical to the real thing, but it’s a good substitute: people familiar with som tam have eaten ours without noticing anything tasting odd :-) Unlike actual dried shrimp, it needs to be stored in the fridge, but it seems to last forever there. We bought it from The Cruelty Free shop in Auckland.

The Red Lotus paste would also be a good substitute for prawn paste and likely for fish paste, too, although those are ingredients we don’t tend to use.

If you want to use dried shrimps for crunch, rather than flavour, I’ve come across the following suggestion (which I’ve not tried): “cut up tofu puffs, deep fry them until crispy, and then coat them in a little bit of salt, sugar, and/or MSG”. Let us know if you give that a go!

Oyster sauce

We haven’t looked into the Thai oyster industry: the NZ oyster industry is fine from a slavery point of view, but, given everything else I’ve seen about seafood in Thailand, I’m skeptical that Thai oysters will be slave free.

However, we still have a bottle of oyster sauce in our pantry. Partly because we use it so rarely it doesn’t seem worth the effort looking for a replacement (a bottle easily lasts us five years!). Partly because I have been unable to find the only suggested substitute I’ve come across (mushroom stirfry sauce) at any of our local Asian supermarkets.

Palm sugar

Palm sugar is generally slave free. Forced labour is a major issue in the sugarcane industry, but Thai palm sugar is made from coconuts, and forced labour and child labour are much less of an issue there. For this reason we are comfortable buying any brand of Thai palm sugar.

Peanuts

Peanuts tend not to be produced using slave labour or child labour, so they are low-risk (although not risk free). We don’t use them a lot in our Thai cooking, so tend to simply buy whatever is available at the supermarket.

Cashew nuts

Child labour is a major issue in the cashew nut industry, and very unsafe working conditions are also common. Because these issues are so extreme, we are careful to buy slave-free cashews even though we tend to use them fairly rarely.

We generally buy cashews from Trade Aid; we also consider cashews from East Bali Cashews to be slave-free.

Chillis

We have not found any major human rights abuses in the production of chillis, so don’t take care to buy any particular brand.

Tamarind

We have not found any major human rights abuses in the production of tamarind either, so buy whatever brand is convenient.

What about other ingredients?

If you’re wanting to cook using ingredients not mentioned above (and not already researched by Just Kai), how can you tell if they’re slave-free?

The first thing I do is check the excellent database of goods produced by child or forced labour from the US Department of Labour. It’s not perfect, but if your ingredient isn’t listed then you can be reasonably confident it’s low risk.

If it is a high risk ingredient, see if you can find someone making a fairly traded version of it - Trade Aid is a good place to look, as is the Fairtrade Australia/New Zealand website.

If you can’t find anything there, see if you can find a version that’s produced in a low-risk country instead (the US Department of Labour website will tell you which the high-risk countries are, so look for something produced anywhere else! Fairtrade and Rainforest Alliance both also produce risk maps for a handful of commodities, which is another useful tool. But it’s best go for a fairly traded version if possible: goods produced in low-risk countries just avoid the problem (as do low-risk substitutes), whereas ones produced fairly in high-risk countries give vulnerable people better options.